All the plants you see here are adapted to alpine conditions.

While we snow-lovers stand to lose from the warming climate, it is the plants and animals living in the High Country that are hit the hardest.

The species that call our mountains home are specially adapted to the unique alpine conditions. Because they live in a distinct climate and altitude, many are found nowhere else in Australia, let alone the world1. As the flora and fauna have evolved to live in a very specific environment, any changes to the mountains will have a big impact on these fragile ecosystems.

Since industrialisation, CO2 levels in the atmosphere have increased by 50%2. While small fluctuations have occurred throughout history, atmospheric CO2 is at its highest concentration in at least 800,000 years3. There is an overwhelming consensus among scientists that this has caused a warming in the Earth’s atmosphere.

High and Dry

As the Earth warms, our mountains are especially feeling the burn. Temperatures are increasing at a greater rate at higher altitudes in south-eastern Australia4.

This warmer and subsequently drier climate in the Alps is not what plants and animals are adapted to. Many are struggling to survive in these new conditions.

The snow gum, an icon of the Aussie mountains, is becoming increasingly drought-stressed. Its weakened immune system is struggling to fight off native beetles that are eating their way through entire forests5. Climate change is shifting the relationships between species that previously lived together in an ecological balance.

Overseas, mountain flora and fauna have been moving to higher altitudes to remain in favourable conditions. The Australian Alps, in comparison, are much lower in elevation and there is nowhere for species to go beyond the mountaintops6. Additionally, alpine ecosystems are being forced to compete with species from below, who are moving up into the now warmer mountains7.

Our High Country ecosystems are being squeezed by climate change. If this continues, we may see a 70% change in species composition of alpine vegetation in the next 50 years8. With it, the mammals, insects, amphibians, birds and reptiles that call these communities home are also under threat.

Alpine ecosystems are in a precarious position. If one species goes, so do others that depend on it and the whole house of cards comes tumbling down.

Snowgum dieback

A Landscape on Fire

The drier conditions as a result of climate change are also providing more fuel for bushfires. As a result, burns have become more frequent in the High Country9. Since 2002, 85% of the Alps have been burnt by several very large fires10.

Bushfires not only drive endangered animals closer to extinction, but also threaten the future of the forests themselves. Fires have always existed within the Australian mountains, however, eucalypt forests need sufficient time between burns to regenerate. Shorter intervals between fires may cause entire ecosystems to collapse, whereby our magnificent eucalypt woodlands completely disappear from an area, replaced by shrubland11.

A Frozen Refuge

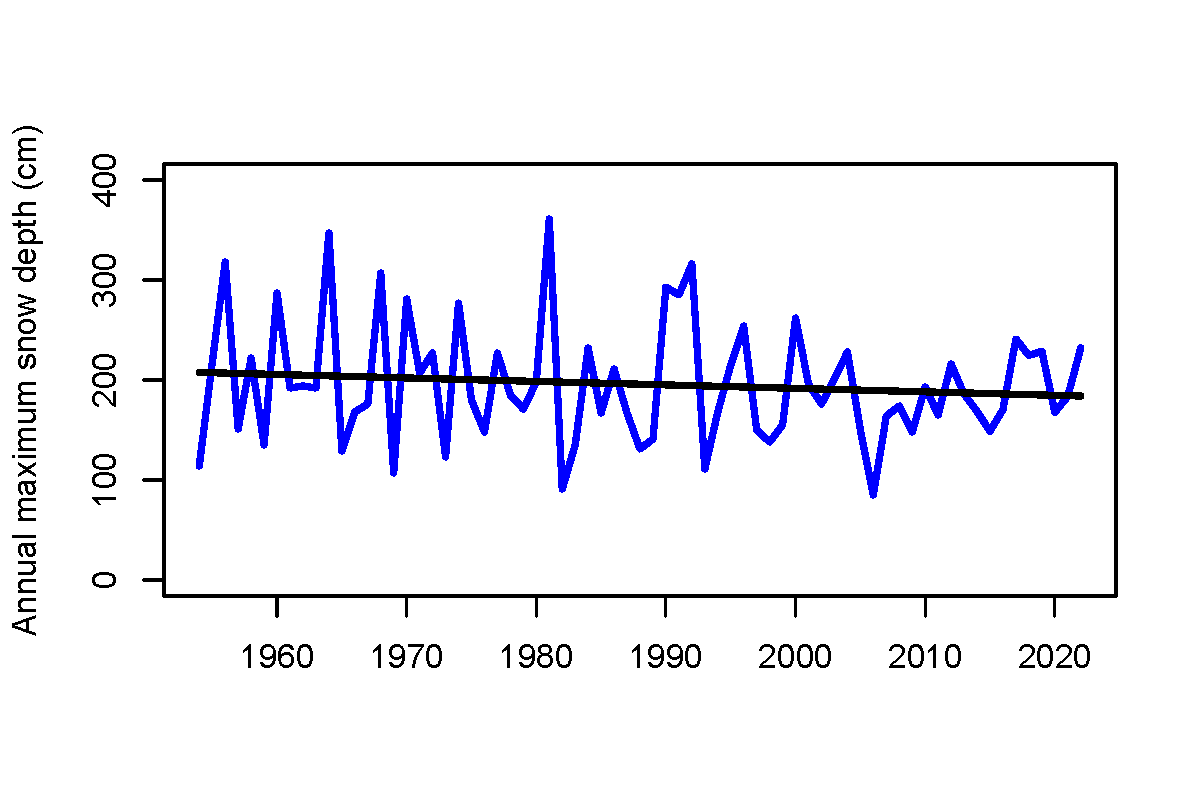

Of course one of the largest changes to our mountains is the loss of our snow. Since human-induced climate change began, the Australian Alps have seen a decrease in snow-depth, less area covered by snow, and increasingly shorter winters12,13.

It is not just skiers and snowboarders affected, but communities of plants and animals that rely on snow for their survival.

One of such species is the critically endangered mountain pygmy possum. Amazingly, it needs the snow to stay warm, hibernating beneath it for up to seven months. Losing our snow would put its lifecycle in jeopardy and risk exposure to the elements and starvation14.

Many plants, and the insects that feed on them, rely on snow patches that persist into the warmer months. The slow-releasing melt from these patches provide water to rare and beautiful communities of alpine vegetation, creating mountain oases15. If the snow continues to disappear, so would the ecosystems that depend on it.

Into the Valleys

The changes to the mountain environment are also felt at lower altitudes. The slow release of water from alpine bogs, fens and forests, in addition to snowmelt, provide natural regulation of water into the Murray Darling-Basin and coastal catchments. This water is vital for river ecosystems across the country16.

A loss of these natural mountain reservoirs may also lead to more significant flooding events in the valleys, with water run-off occurring at a greater rate17,18.

Our Responsibility

Our mountains have changed dramatically since human-induced climate change began, faster than its ecosystems can evolve. We must protect our beloved environments in the face of our new reality, especially as they are our natural ally in combating climate change. These ecosystems naturally draw CO2 from the atmosphere, with Australia’s mountain ash woodlands being the most carbon dense forests in the world19.

It is vital that we do not allow any more harmful changes to occur. We have a responsibility to listen to the best available science and stop releasing CO2 into the atmosphere in order to save our mountains.

Further Reading

- Kosciuszko National Park Plan of Management

- Carbon Dioxide Now More Than 50% Higher Than Pre-Industrial Levels

- IPCC AR6 WGI Chapter 03

- Article on rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- The Aussie Snow Gum: An Icon in Trouble

- Climate Change Impacts Alpine Biodiversity

- 1600 Years Ago, Climate Change Hit the Australian Alps

- Climate Change Impacts Alpine Biodiversity (Revised)

- Climate Change is Bringing Bushfires More Often

- An Icon at Risk (PDF)

- Article on www.pnas.org

- CSIRO Publication

- Abstract on www.int-res.com

- Mountain Pygmy Possum Recovery Plan

- UC Researcher Finds Climate Change is Melting Valuable Snowpatches

- Climate Change Impacts Alpine Water Availability

- Article on agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- Peatlands Protect Against Wildfire and Flooding

- Article on www.pnas.org